Wayward exhibition 2008

By Abby Cunnane

Janne Land Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand (8 April – 26 April) 2008

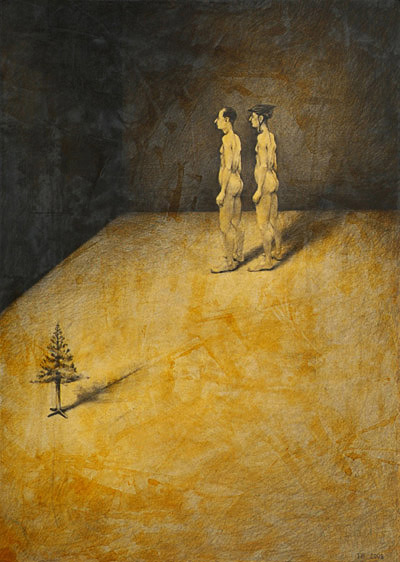

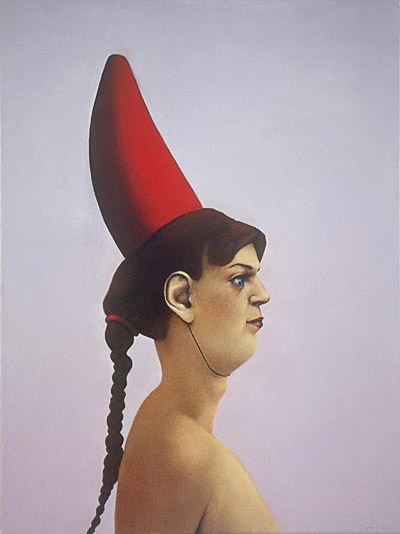

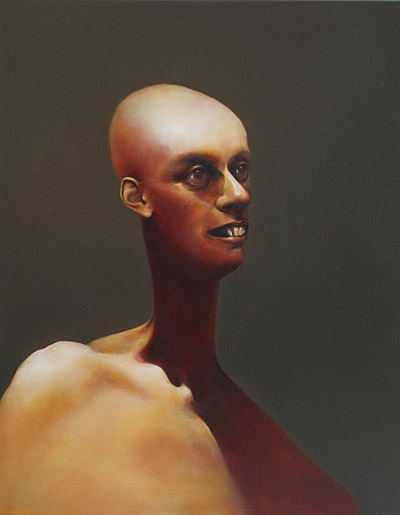

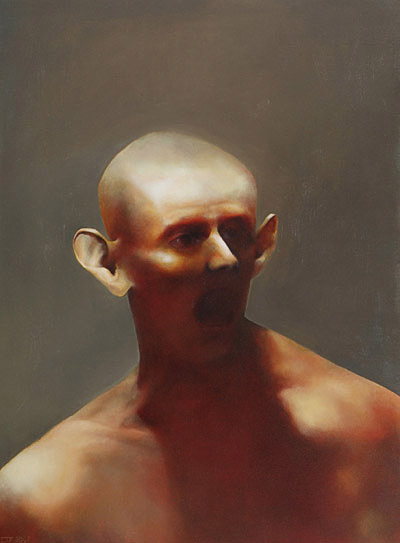

The closer you approach certain images the softer you tread. Irene Ferguson’s recent portraiture has this effect: their intensity bordering on intimidation, perhaps because despite their individual peculiarity they remain unabashed. ‘Wayward’ (Janne Land Gallery, Wellington) consists of a suite of large portraits accompanied by smaller works, charcoal drawings and oils. The grouping is interesting, paralleling quasi-mythological figures with quietly surreal dollhouse-sized images of trees, a carpark and a museum. Ferguson’s figures seem to have outgrown this toy-like artificial landscape, and stand with unnerving self-composure.

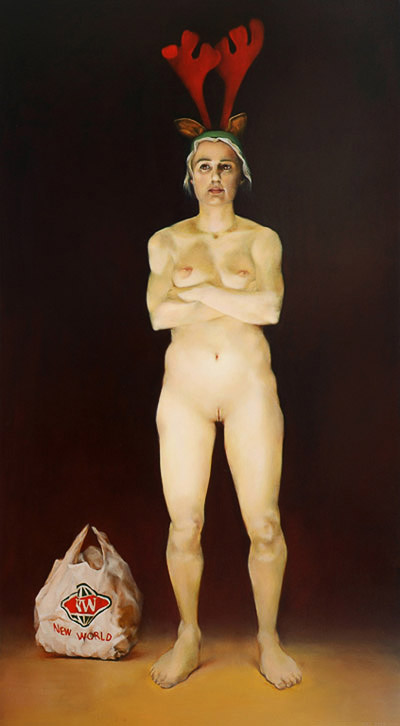

Of the portraits in ‘Wayward’ it is Diana and Daniel, which arrest. The pair gives us a sense of contemporised mythological figures, classically posed in their unlikely costumes. Diana, in soft reindeer antlers, stands naked and up-lit as if by the glow of a fire. Roman goddess of the hunt, of chastity, of fertility, this antlered-Diana is standing beside a plastic New World bag, which she appears to have dumped unceremoniously. Arms folded, she looks unimpressed at the situation. Is she a contemporary huntress, a disgruntled artist’s model, or perhaps just someone at the end of a long day caught between guises – shopper, performer, and goddess off duty? As we await the verdict of her cool appraising gaze, we become aware of the unusual situation; how is it that a hood and antlers, nakedness and the appearance of having been shopping recently fails to equate to ridiculousness? The B grade Eve is a commanding figure.

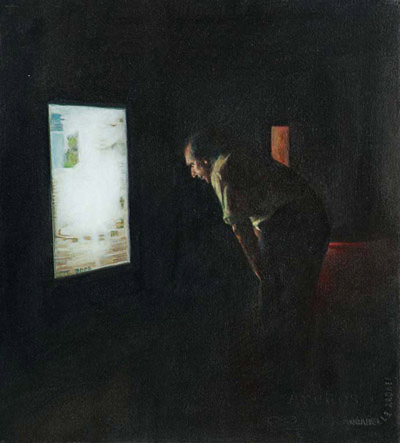

Daniel, ‘Adam’ to her Eve, is similarly provocative. Again adopting a classical pose, he is unclothed except for underpants depicting the US flag. Presented with his profile, we can see the fine modeling that reveals this artist’s training in figure drawing. The light here is cooler, the ground dark, and the skin tone not flawlessly finished. By contrast with Diana he is diminished; his is a less confrontational stance, yet this older work raises its own questions. Is he an aging extra engaged in his own private drama; are we privy to a performance of comic or ritual nature? The American flag underpants suggest an emperor’s new clothes analogy; yet evoke little desire to laugh. In this way Daniel confounds the viewer, eludes the exposure of the nude model, and gives away little.

As recent recipient of the 2008 Adam Portraiture Award, one might have expected Ferguson to offer more along the lines of her winning work The Blue Girl. Yet while these portraits are not entirely dissimilar, they reflect new concerns: the subject as role player, the de-stabilising of sitter/viewer relationship, mythological or contemporary symbolism dealt with in an ambiguous yet light-handed manner. They are underpinned by the distorted magic-realism seen in works such as The Sister, Flycatcher or Chicken Man, which Ferguson-followers are familiar with, and even older work such as the Braille series, which featured fleshy or scarred surfaces.

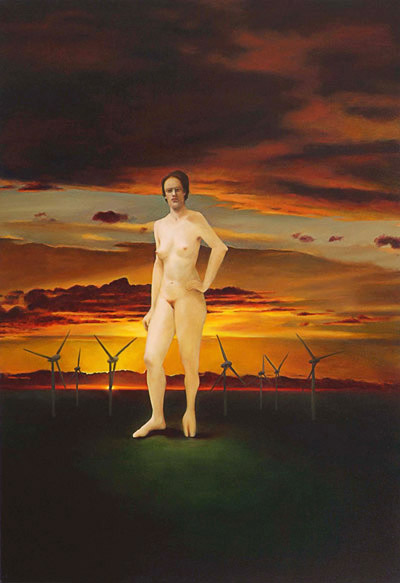

Gabriela, among the new works, powerfully connects all these threads. Set in what appears to be a wind farm at the end of time, the white-skinned figure quotes her namesake’s role of apocalyptic messenger. On closer inspection we see she has one cloven foot, a strange hoofed angel, striking the pose of a contemporary Jean Harlow.

The drawings occupy another place, and another scale. Foyer, a small charcoal depicting a diminutive tree set in a table, could almost be called playful if it wasn’t simultaneously rather pathetic. Conifer on the other hand may be a gargantuan Christmas tree, or an outsize stage-prop were it not so deftly placed centre stage. Making subtle statements about the consumption of the ‘natural’, they refuse to be purely ornamental. Carpark (recognisable from Thorndon New World) is loosely reminiscent of an Edward Hopper work, a surreal ode to modernism, and just the place where Gabriela may next alight after the wind farm, or Diana may have sourced her groceries.

With no small debt to the theatrical, or to the darker side of filmography by Michel Gondry or Jean-Pierre Jeunet, this show retains its own very distinct place. Despite the multiple allusions within the works, the guises and distortions, we are unable to shake off the awareness that they are pictures of real people. Fictions in one sense, they have potency in part because they started ‘life’ as portraits. From an artist whose work has refused to stay still, ‘Wayward’ is consistent with the trend.