Witness exhibition 2012

By Dr. Warren Feeney

Hastings City Art Gallery, Hastings, New Zealand (1 September – 11 November) 2012

To assume that the paintings of Irene Ferguson and Emma Pratt are figurative, detailing the artists’ experiences of the world is accurate as it is misleading.

In her attention to the small detail of the narratives and allegories that inhabit Ferguson’s imagery, she frequently gives due attention to familiar traditions of painting from Western art, yet the curious cut-and-paste realization of these works seem to be as much about respecting the art and culture of Europe as they are about drawing attention to the art of painting itself, as the supreme act of deception.

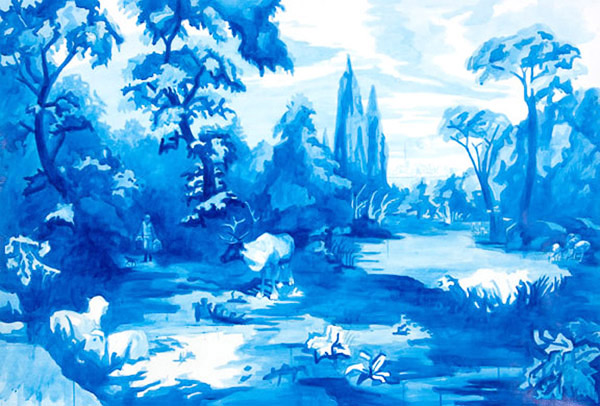

And although there may be a stillness and underlying order to the townscapes of Emma Pratt’s paintings, there is also a pervasive sense that she is an artist simultaneously setting out to deface or take apart an iconography that seems almost too precise, too composed and somehow not quite at home. Yet, Pratt’s images also seem better for the implication of such a wish- a desire for more or something else that is just about to take place again, on the surface of the picture plane.

Witness might better be described as an exhibition of figurative paintings that deals with the nature of our experiences of the world as it deals to-and questions- the very act of painting as a means to encapsulate the tasks and principles it represents. It is no coincidence that both Ferguson and Pratt seem conscious of their role as artists and makers of figurative images, a tradition in the fine arts informed by well-known conventions predominate from the Renaissance to the late 19th century. Yet, references to social realism, 19th century landscape painting, classicism, formalism, postmodernism or expressionism, also willingly recognize the value of such conventions as ideas that may be disassemble and reconfigured in ways that appear relevant and pertinent to their own experience. Are the paintings of Ferguson and Pratt a witness to humanity’s experience in a global community in the 21st century, offering a sincere and first-hand account of such? Yes, but they offer even more.

Ferguson and Pratt make works that shift and fluctuate in their consideration of subjects and the context of all possibilities. If Ferguson’s imagery is a composite of references that take in snapshots of the sublime, literature, cinema, painting and photography, Pratt’s art is assembled from an iconography that seems both nostalgic and actual – as much about the ephemeral nature of memory as it is about the here-and-now, even to the point of the presence of paint as substance on the surface of the picture plane.

In Witness, certainty and suspicion appear to ocupy the same space. Ferguson locates subjects, objects, conventions and values through time and space, resolving all their differences of opinion, yet she equally observes that she sees herself constantly wanting to…’be some other place.’ Pratt’s paintings of Seville- the work of an expatriate from New Zealand now resident in Spain – are described by her as ‘personal travel maps’ yet they are also work by an artist who is living abroad – and by choice recognizes that she is an outsider.

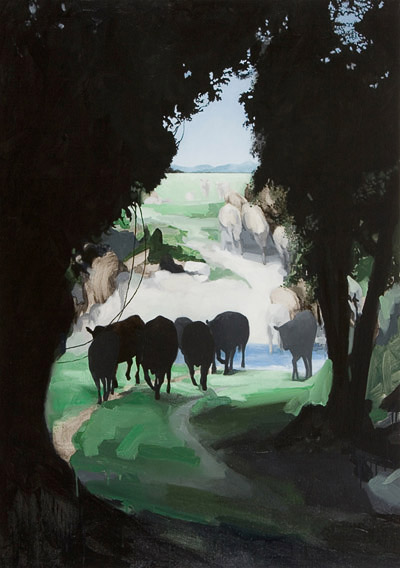

How to make sense of this assemblage of distances, beliefs and encounters? It is a question that both artists direct back towards the audience in the gallery. Ferguson’s art is a celebration, (even a eulogy), to painting as deception – an unreality of our experience of the world in which we live. In Dorothy Falls, Ferguson’s pastiche of an idyllic pastoral landscape, her attention to detail, the treatment of light, and collage of contemporary and historical references, could all be part of a long-lost parable or a peculiarly modern fairy tale. And in making the question of this painting’s intention a subject up for debate, Ferguson turns the viewer’s attention back upon them. Implicitly, we are required to occupy the same stage as the figures that inhibit her paintings. Ferguson’s subject becomes how to read, decode and make sense of a narrative that is overtly layered and oblique. She also notes that is not just the content of her work that is critical to this experience, but also the physicality of her paintings, occupying the gallery space, maintaining a ‘presence…but also (being) not of this world’:

I like that moment when as a viewer you stand in front of a painting. Perhaps it’s the spot where the artist stood and you see the abstract nature of the paint and feel the physical act of mark making that has made this image. The paint will assist the image to hover between the real and the abstract.

Pratt’s imagery is no less demanding; digital images, videos and photographs, all coalesce to seek out and locate a place that might seem like home. This is an idyllic and elusive world. Pratt observes:

My work has its basis predominately in landscape with, at times, other images which help portray my mythologies and cosmologies. Images have been sources from stills uploaded online from webcams, video stills, quick shots out of a car window, old photograph albums, all catching the fleeting, the changing, the expanding and the eternal. I trace the existence of many worlds or ways of seeing: a nostalgic past, where “home” is, shadowy pasts where I was not, and an ever increasing, global present.

Ferguson and Pratt are in good company. Their consideration of painting as a conduit for ‘ways of seeing’ has its own close association with Spain, a country where Pratt has lived since 2000 and both artists worked together. Diego Velázquez’s painting of the Madrid Place and court of King Philip IV of Spain, Las Meninas is a work that also addresses essential questions about painting’s representation of the world and the viewer’s relationship with a work of art. Famously, as Velázquez looks out at the viewer in his work, his audience becomes aware that they are both looking, and being looked at, similarly confronting them as the subject of the painting.

And if Ferguson and Pratt can be described as artists whose practice both belongs to – and is separated in time and place from the grand traditions of European art, the paintings in Witness, are equally a part of- and distanced from- New Zealand’s art history. Pratt is an expatriate New Zealander and former artist-in-residence in San Lucar de Barrameda. She meet Ferguson in 2008 in Seville when she was the recent recipient of the Portrait Award from the Adam Art Gallery. Both artists seem to willingly acknowledge a cultural distance that continues to look their was just as it did for expatriate artists in the mid-twentieth century. Ferguson currently lives in New Zealand and misses the contact with Spainish art and its traditions, while Pratt –as a longstanding resident in Seville – acknowledges that she misses the landscape of New Zealand. It’s a sentiment perfectly summarized almost 100 years ago by Frances Hodgkins as she reflected on her departure from the place of her birth:

Perhaps I ought to have been content with what was a very interesting life, but I felt I was only groping: that I had not realized myself.

Working between countries, connecting via the internet to discuss their painting with one another, there is a degree of both intimacy and distance in such a relationship. Pratt assembles images of a place somewhere far away, consistently on the edge of perfect realization, erasure and reconfiguration. Ferguson’s art seems to draw from all four corners of the globe, virtual and otherwise through time and space. Yet, both make works that are as specific as they are representative of a state of flux and permutation – A first-hand account- if you like- of paying witness to a poignant, tangible and ultimately transitory experience of being.